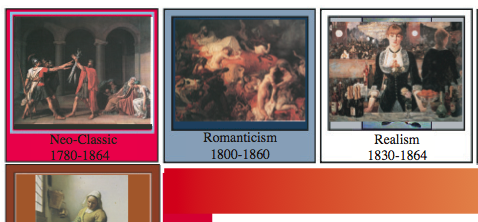

The sixth session of the “Art is Us” art history class for Spring 2015 was held on Thursday, April 23. We discussed the homework assignment, a comparison of Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Manet’s Olympia. The presentation covers artwork from the Neo-Classic, Romantic, and Realist periods. In Neo-Classic work we see a return of characteristics from the Greek Classic and Renaissance periods, and a return of Greek Hellenistic and Baroque in Romantic, both with new interpretation and worldview. The Realist movement takes a whole new approach, of “art for art’s sake,” rather than to represent the world around us. Works by Ingres, David, Gericault, Delacroix, Turner, Millet, Courbet, Manet, and others are featured. For homework, there is a quiz, and new comparison and tribes homework assignments.

Homework assignment

Here are the homework assignments for next week: a quiz, compare two artworks, and a new Tribes game.

Class recap – some key ideas

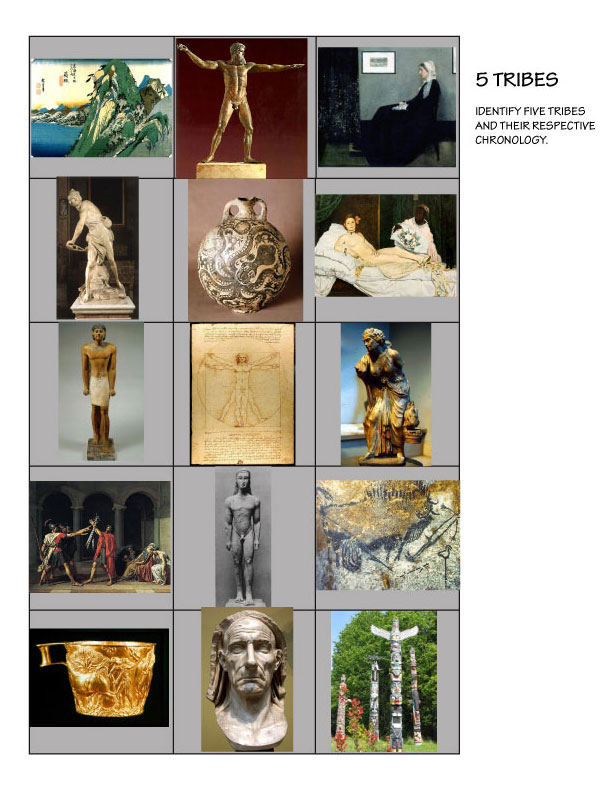

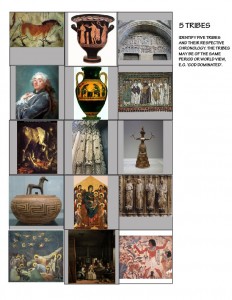

“Tribes” homework

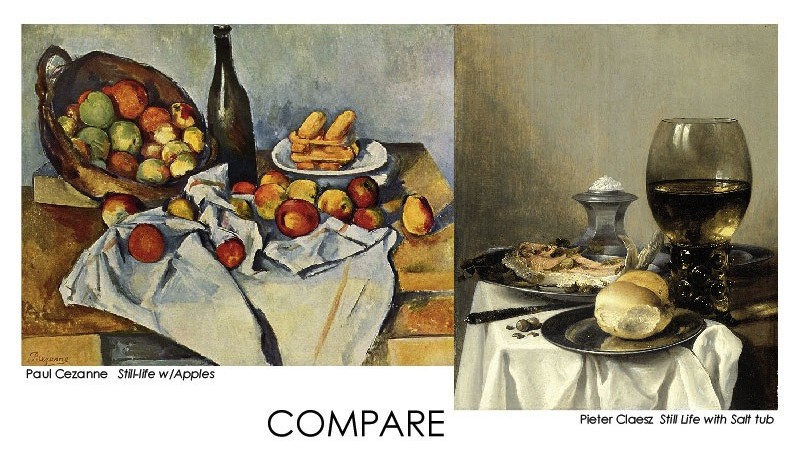

Comparison homework discussion

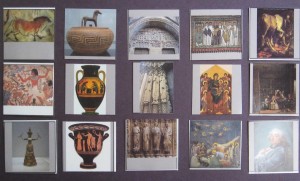

The homework assignment was to compare two paintings, Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Manet’s Olympia.

Here we have two similar compositions on the same theme, with major differences in interpretation. On the left, Titian painted a classic, idealized, Renaissance painting. On the right, Manet had a whole new subject: the painting itself. The eye first registers the starkly contrasting shapes in almost-white and almost-black. Paint on canvas is what is real, giving name to a new movement in art, Realism. This was the first recognition that a painting did not have to “re”-present something, it could just “present” itself, like a table doesn’t “represent” anything, it is just a table. As an artist, Dick is making marks that communicate in concert with the other colors and shapes around them. If you ask of this painting, “What is it?” the answer is, it is a lot of white, and a lot of black. First and foremost, there is contrast in value. (Listen to part 1 of the audio files, below, for much more detail from this discussion.)

Comparison poem: Two Nudes, by Two Dudes

Titian’s Venus of Urbino, quite conventional His look to the classics was intentional Her idealized beauty so un-missable It assured his Venus to be Salon admissible Manet’s Olympia, stunning, inventional, His break with the norms was quite intentional. The Salon was shocked and declared, "un-admissible!" "A homely prostitute with a face that’s un-kissable!" If beauty is truth and truth is beauty, Can we choose which painter did his duty? Each painted the truth that was his vision Titian met praise, Manet derision What can we say about each decision? Titian’s tradition pleased contemporary peers Manet changed how we see art in coming years Titian loved the past, and he stuck to it Manet saw the future…”See my painting, not through it”

Steve Goldstein, the poem’s author, said “This little poem is dedicated to Dick Nelson, our beloved Art-is-Us mentor,” 4/23/15.

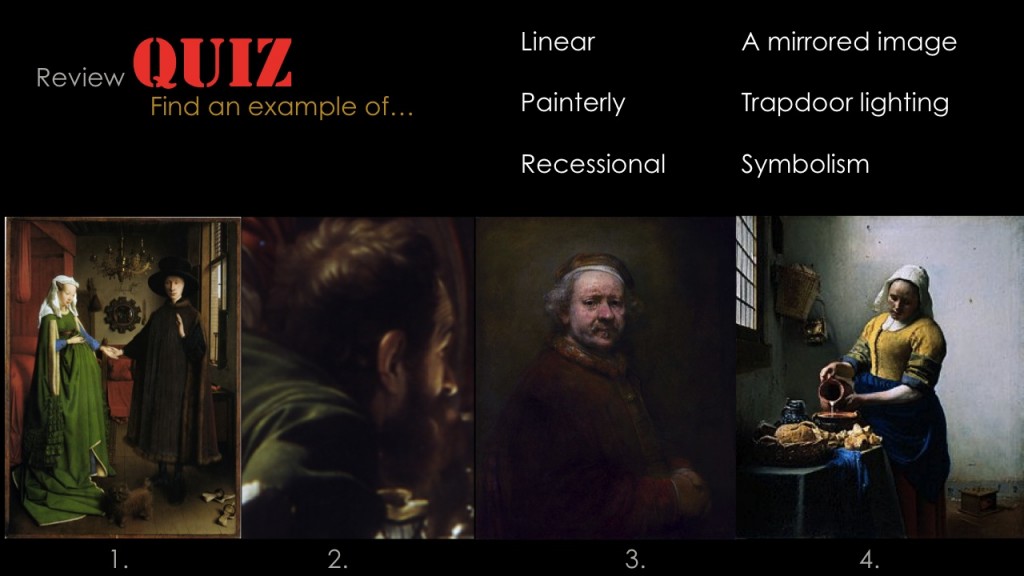

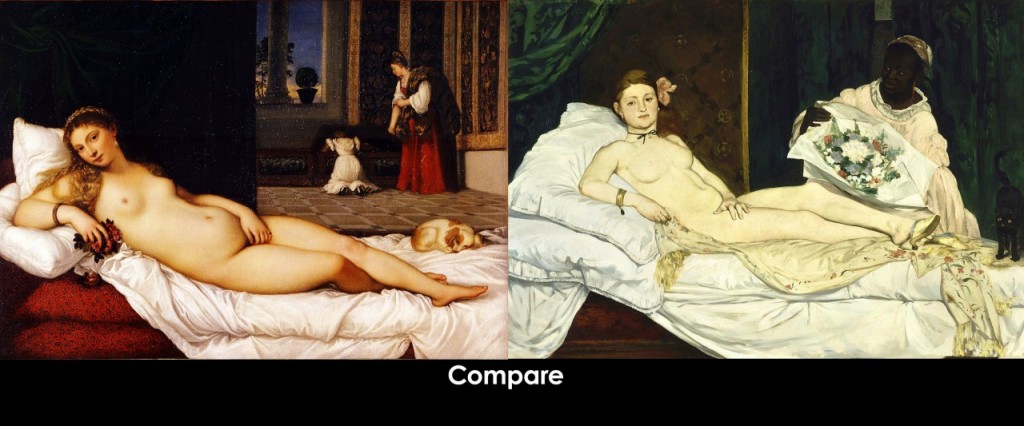

Wölfflin’s principles of art history

One person requested more information on Heinrich Wölfflin’s “painterly” principle discussed last week. All five principles are discussed here, with a comparison of two images. Wikipedia has links to artists who exemplify the painterly characteristic. The five principles, which Wölfflin applies to sculpture and architecture as well as painting, are

One person requested more information on Heinrich Wölfflin’s “painterly” principle discussed last week. All five principles are discussed here, with a comparison of two images. Wikipedia has links to artists who exemplify the painterly characteristic. The five principles, which Wölfflin applies to sculpture and architecture as well as painting, are

- Linear / Painterly

- Plane / Recession

- Closed form / Open form

- Multiplicity / Unity

- Clearness / Unclearness

Wölfflin’s book is still in print.

Class materials

Lecture and slideshow: Neo-Classic, Romantic, Realist

A brief commentary on each slide is provided here; listen to part 2 of the audio files, below, for more detail.

- Cover slide, lecture 6: Breaking the Mold

- Review quiz (not discussed; assigned as homework)

- Comparison homework discussed above

- Here we see paintings with the same theme, shaped by different interpretations. You can see the how the Neo-Classic painting by Ingres on the top right has similar qualities to Titian’s painting from the Renaissance on the top left. The Romantic painting on the lower left has echoes of Baroque interpretation, while Manet’s painting from the Realist movement takes a completely new direction. In the next few slides we’ll move quickly through the periods between Titian and Manet: Neo-Classicism and Romanticism. These periods will become more than labels as you begin to recognize recurring principles and distinguishing characteristics.

- This Neo-Classic painting, Odalisque by Ingres, has these qualities in common with Classic Greek and the Renaissance: linear, planar, time stopped, attention to detail. The figure is modeled without any suggestion of brush strokes.

- This drawing demonstrates form carefully defined by line. Dick loves drawings because they show the thinking process of the artist.

- Here is another painting by Ingres. It looks realistic, in terms of carefully rendering human form, furniture, landscape, lighting – but the scene of a harem is hardly from everyday life. What is real is the illusion that we are in this imaginative scene. The artist really understands perspective, light, anatomy; he did a masterful job.

- This is a portrait of a notorious banker. The artist communicates his personality through his creative choices.

- Ingres was a master visual communicator, using visual devices for emphasis: your eye is drawn to the white, claw-like hands due to the strong contrast against the black clothing.

- Notice the classic characteristics in this Neo-Classic work: linear, planar, closed form. The perspective lines point to the swords, the center of interest. It has all the elements we saw in the Renaissance, except for the Christian storytelling.

- In the Age of Reason, we see Classic characteristics again. They are diagrammed and listed in this slide. Notice the classic figures, with generalized faces.

- The death of Socrates, an imagined scene from Greek history, depicted at the climax, the moment of decision: “This I will do.” It displays other characteristics of classicism: linear, planar, idealized.

- It exemplifies the relationship between what the artist believes and how he presents it. Unlike the typical “light of day” of the Renaissance, the lighting in this painting shows the influence of the Baroque, which this artist would have been familiar with. Each age draws on the past.

- Now we move into the Romantic period. A dramatic scene of a contemporary tragedy is depicted, at which the artist was not present – he had to use his imagination, and make thousands of decisions on shapes, locations, colors and values. Unlike the Neo-Classic, this is meant to really engage the viewer on an emotional level. The Romantic period followed right after the Neo-Classic. They both represent eternal human tendencies, inherent in each of us. Dick said, “I am both reasonable and passionate, at different times. Know in your own heart and mind, where are you?”

- This artist has used strong contrast with purpose.

- Delacroix suggests, without painting it all out.

- Sequential periods, Neo-Classicism and Romanticism, compared.

- Romantic painters depicted life-and-death scenes, not scenes of daily life. Notice the undulating, moving qualities in this dramatic scene.

- To Dick, J.M.W. Turner’s Fighting Temeraire is one of the great paintings in art. (add more here! also link to commentary from 2009)

- Turner’s work shows his interest in observing qualities of light and atmosphere, recreating a moment or an impression, more than an exact representation of a real or imagined scene.

- Painters began showing an interest in ordinary people, not just aristocracy and heroic scenes. Artistic choices convey respect for these ordinary people.

- Two scenes of laborers. The left scene is monumental and poetic, the right more grubby and candid. As an artist, you choose what you want to communicate, and how to reach your audience. Neither of these scenes would have been painted in earlier times, signaling a change in the social order.

- A closer look at Courbet’s Stone Breakers.

- Paintings on this monumental scale were usually of aristocracy or heroic scenes. This was a burial of a common person, depicting the artist’s family. In a prelude to Manet, things are flattening out; there is less depth in the atmosphere and shadows.

- Courbet injects some of the same elements we see later in Manet. There is a change in subject: these were writers of fame, allegorically gathered on one stage. The painting takes on new importance as a painting, not just a replication of reality.

- Manet drew inspiration from Titian’s composition, but he was more interested in the picture than the story. Rather than idealized, classical figures, his models were particular, identifiable Parisians.

- Comparing Titian’s and Manet’s compositions again.

- We discussed this one in depth earlier, in the comparison assignment. Manet was the first “Realist” painter, interested in the reality of the painting as paint on canvas: a composition of shapes, light and dark, color.

- Artists of this time became obsessed with Japanese prints, with their flat, stylized, poetic shapes. They recognized that art could do more than try to fool the eye with illusions of reality. This was the prelude to all of modern art.

- But, with recognizable subjects, it still has a foot in the past – it is an evolution of style.

- Manet conveys more than one point of view through use of the mirror behind the wistful barmaid. He was a very important link between the art traditions of the past, and modern art to follow.

- Movie: Red on Stage: portraying an apple, a barn, and finally – himself. In modern art, we’re really off course if we ask, “What is it?” It isn’t supposed to be something other than what it is. We don’t ask of music, “What is it?” It is allowed to simply be itself.

The 2009 version:

Audio files

Part 1, Comparison homework and slides 1-3 (50:39)

Part 2, Lecture on the Neo-Classic, Romantic, and Realist periods, slides 4-32 (1:01:37)