The first session of the “Art is Us” art history class for Spring 2015 was held on Thursday, March 19, with 15 people attending. Dick’s goal for the course is for students to develop an eye for independent viewing of any artwork, to be able to look at any painting and bring an objective analysis to it – more than just “I like it” or “I don’t like it.” Dick is an artist, not an art historian, and will emphasize visual and tactile aspects. The course is not about names, dates, and other facts, which can be easily found on the internet and need not be memorized.

Homework assignment

Your homework for this week is:

- Go through the art history game DVD you received in class. It should only take about 30 minutes. Feel free to repeat several times during the week, or pause as you go along. You will easily develop a cognitive structure for the chronology of art history that will be useful through the next eight weeks and beyond.

- Observe homes, gardens and landscaping. See if you can find one example which is geometric and controlled, and another where natural growth is encouraged. Optionally, take photos and email them to Karen to share in class next week.

Class recap – some key ideas

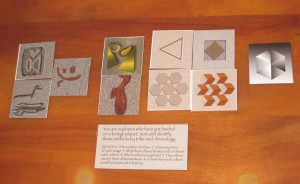

Art explorer game – sorting artifacts

Five groups of three people each were given ten image “artifacts” and these instructions:

You are explorers who have just landed on a foreign planet. Sort and identify these artifacts by tribe and chronology. Identify:

- The number of tribes.

- Characteristics of each image.

- What these characteristics tell us about each culture.

- Which culture is superior?

- The criteria used in these determinations.

- A name for each culture as well as its period in history.

Each of the five groups came up with different groupings and chronologies, prompting Dick to comment “So, you see how you’re all in lockstep?! What does this begin to tell you about art historians?” The number of tribes identified ranged from 2 to 5. Dick pointed out some clues to chronology. Identify the givens – what are they working with? What constraints do the materials impose? The earliest works will use the givens most directly. Later works will show evidence of more sophisticated forming processes. In doing this analysis, stick to the IS – what you can see objectively and describe factually. Stay away from judgment and OUGHT. Don’t impose your values and assumptions. Just because a culture is different does not make it bad or inferior.

Some more questions to ask: What does the evidence you’ve observed tell you about the person and culture that created it? What was in their environment? What are the root causes? What is important to them? What is central to the core of their whole being?

(We’re still missing a photo of one group’s sort – please send!)

Introduction to the art history game DVD

The art history game, on DVD or physical cards, is designed to help develop a cognitive structure for the chronology of art history. Just as anyone who has played the Monopoly board game can picture the color and location of Park Place, you will unconsciously develop the same kind of intuitive placement for periods in art history. You’ll be able to picture which side and color are associated with the Renaissance, for example, or Impressionism. Art takes different forms through the ages because people value different things and have different world views. As we go through the course, Dick will point out identifying characteristics of different ages.

[gview file=”https://dicknelsoncolor.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/AH-GAMEBOARD-PLUS-2015.pdf”]

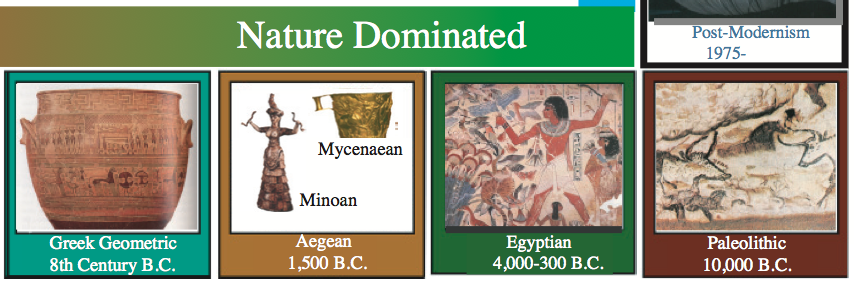

Lecture & slideshow: Nature and Man in Art

Here are some points Dick made about each slide.

- Beliefs shape art. The givens shape art.

- How sophisticated are these people? They’re depicting an animal in motion – not easy! They consistently use a break in the outline to indicate which leg is closer to us – depth.

- What are the similarities and differences to the previous image? Look at the differences in the rendering of the animal and the man. The detailed and accurate rendering of the animal suggests how important it was – even more important than the man, who is merely a petroglyph. Angles of lines tell us about the dynamics of the scene. Verticals and horizontals are static; diagonals are dynamic. The man, at a diagonal, seems to be falling, perhaps because of the animal’s charge, indicated by the forward diagonal thrust of the fore quarters. However, the hind quarters are vertical, static, dying – the animal was pierced by a spear (on the opposite diagonal) and is spilling its entrails.

- One figure clearly dominates the left scene. The pharaoh is important in the painting because he was important in the culture. Other figures are drawn smaller, in proportion to their significance, not to their sizes in real life. Is there something else strange with the perspective? The pharaoh’s face is in profile, but his eye is drawn as if facing forward. The chest faces us, but the arms and legs are in profile, going toward our left. Each body part is drawn so it is the most recognizable, not the most realistic. Multiple pieces of evidence tell us that the ancient Egyptians were more concerned with depicting significance or meaning than realistic appearance.

We see something similar in children’s drawings. The sky is drawn along the top of the page because the most important – the most real, to the child – thing about sky is that it is up. These artists are not trying to replicate what they see, but tell us more than what we can see – tell us what is important. - The formal, stylized poses suggest that these societies may be governed by strict rules. The figures’ “arrested walk” is limited by forces outside the individual, and by the material from which they are formed.

- The posts’ decorative tops mask their functional role in supporting the lintel beam. Solid stone has a light and airy appearance.

- The flared tops of the Minoan columns also hide (from a ground-based observer) their role as vertical supports.

- The conical shape of the snake goddess comes from being carved from ivory. The bull’s head seems less inhibited by material constraints.

- Art historian Vince Scully deduced that the long axes of important Minoan buildings pointed toward a mountain which resembled bull’s horns.

- Athletic feats involving a bull. The bull was clearly important in Minoan society. Man at this point, as also seen in Athens, is at an adolescent stage – somewhat insignificant, and trying to come to grips with nature, a more powerful force.

- Large clay vessels with surface decorations which mimic or suggest nature

- Giant clay vessels, with practical and decorative handles

- Mycenaean gold cellature

- Mycenaean lion gate

- While the Minoan octopus vase has organic curves in contrast to the lines and angles of the Greek geometric vessel, both show an interest in figure-ground relationship, and high sophistication of design. The white space is as exciting as that which was painted.

An interesting question was posed: These are both beautifully done, and serve a practical purpose. Are other members of the same society eating and drinking from similar, but plainer, pieces? - Transition – The Greeks – coming soon!

The 2009 version: